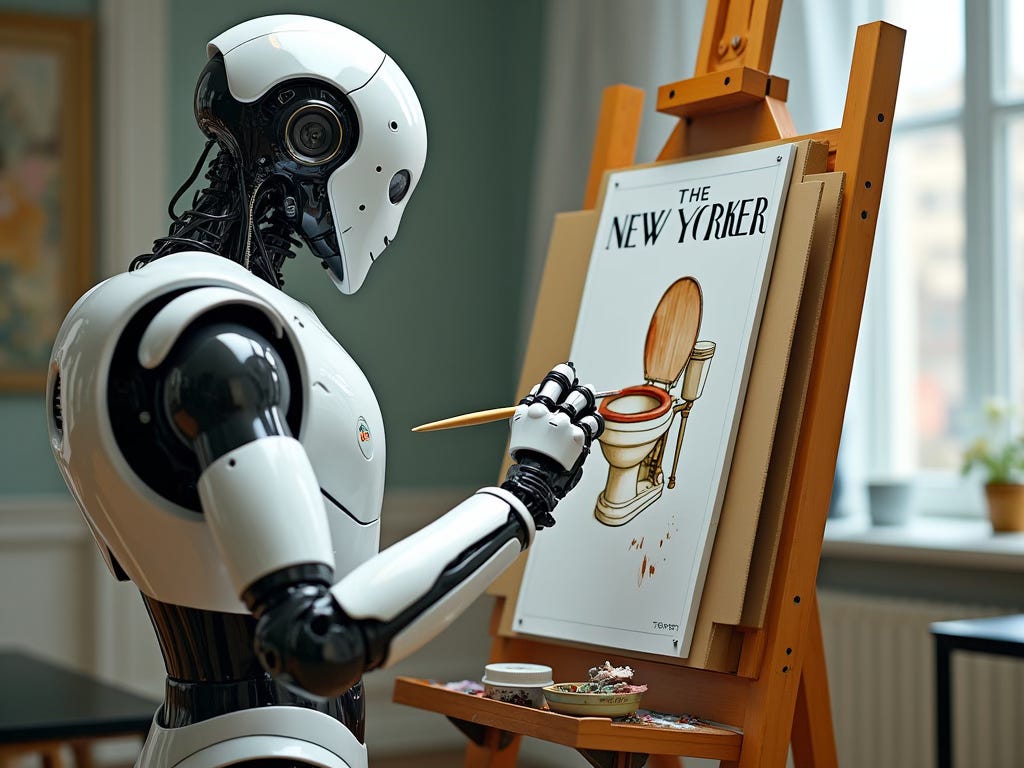

Yes, A.I. Will Absolutely Make Art

Ted Chiang’s New Yorker article is incorrect, maybe dangerously so.

Ted Chiang, the acclaimed science fiction author behind "Story of Your Life" (adapted into the 2016 film "Arrival"), recently penned an article for The New Yorker entitled "Why A.I. Isn't Going to Make Art." Chiang argues that human-made art will always be superior to AI-generated art. His reason…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Code and Context to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.